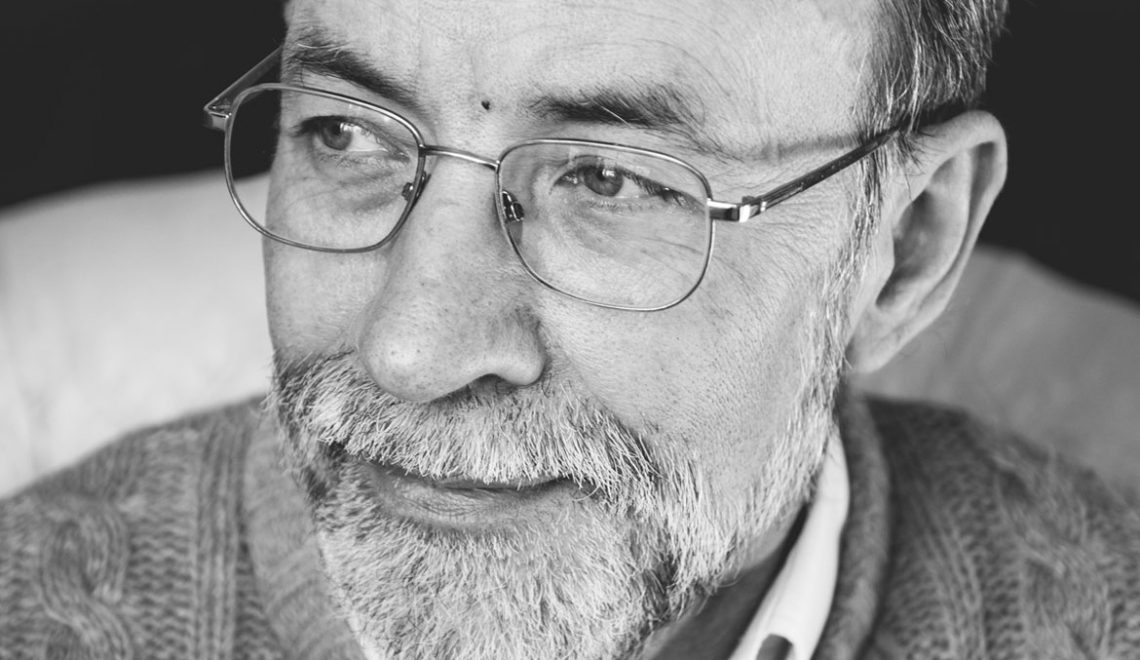

Lee McIntyre is a Research Fellow at the Center for Philosophy and History of Science at Boston University and an Instructor in Ethics at Harvard Extension School. In addition to that, he is the author of some fantastic books including, The Scientific Attitude (2019) and Post-Truth (2018). In this interview, we have touched on a wide range of topics from his upbringing in Portland, Oregon, to his favourite books, spoiler alert – one of them is Walden by Henry David Thoreau. It has been an absolute privilege to interview Lee, it’s a really fun read and we hope you enjoy it.

Jump to: Books Recommended by Dr Lee McIntyre

Introduction

Q: What is your dinner party monologue for when someone says “and what do you do?”

A: I usually say “I’m a philosopher.” If they’re ready to hear more I say “I’m a philosopher of science and I’m particularly interested in what’s special about science and how we can use that to fight back against science denial.” At that point, they’re either intrigued or they head for the canapes.

Early Life

Q: Could you tell us about where you grew up; were you a rural or city dweller?

A: I lived just outside the city limits, near the airport, in Portland, Oregon. It was a tough, working-class neighbourhood. Tattoo parlours, strip joints — and the local motorcycle gang had their clubhouse in the duplex across the street. For high school, I had the biggest break of my life and went to the Catlin Gabel School. It was the fancy “rich kid’s” school that was two bus rides away across town, but I went there on a full scholarship. I loved it there, but I had a lot of ground to make up.

Q: What subject(s) did you excel at in school, and which did you find most challenging?

A: I’ve always enjoyed the written word, so I did well in English and history, but I aspired to be a better writer. I loved science too. Foreign language was my nemesis. It just never made any sense. All those irregular verbs (in French). There was no system, no order. When I finally took logic in graduate school it was like “ah, I’m home.”

Foreign language was my nemesis. It just never made any sense.

Q: Can you recall any reoccurring comments from your school reports?

A: Responsible and conscientious. I knew from an early age that education was my ticket out. I took school seriously. I had a lot of examples of people who had made bad choices all around me in my neighbourhood and I didn’t want to be “that guy.” Fortunately, my family always valued education, so I had an encyclopedia and a desk. My parents never went to college, but all four of their kids did.

Q: Did you ever have a eureka moment where you thought, “this is the subject I want to study”?

A: Oh yes! I was sitting in a carrel on the top floor of Olin Library at Wesleyan University reading Karl Popper’s Conjectures and Refutations. It was electric. I thought “this is what I want to do….this is the secret to making the world a better place. Defending science.”

Academic Education

Regarding your undergraduate studies:

Q: Which University did you study at, and was it your first choice?

A: I got my B.A. at Wesleyan University, which was an ideal place for me. At 17, of course, I wanted to go to Yale or Princeton like so many of my classmates. Now I wouldn’t change a thing. At Wesleyan, I found a mentor and decided on my life’s work. I also met my wife on the first day of college. Enough said.

Q: What undergraduate degree did you study for at University, and in hindsight would you select the same subject again?

A: I made up my own major (in typical Wesleyan fashion) on “the comparison between natural and social science.” It was a great choice because it made me responsible for my own education. I never studied anything I didn’t want to; I never wasted a course. But I ended up taking classes in 14 different departments including economics, history, math, physics, and music. It was the best thing I could have done…..until it was time to apply for philosophy graduate school and they said: “what the hell is this?”

Q: Can you remember a University lecturer who really inspired you?

A: Richard Adelstein, in the economics department at Wesleyan. He is a first-class teacher who became a friend. I not only took his classes, but he invited me to Thanksgiving dinner at his house every year. Even after college, I kept going back, with my wife and kids. Years later, I started to invite my own students to my house for Thanksgiving. So he inspired me not only as a teacher but as a human being.

Regarding your postgraduate studies:

Q: What motivated you to further pursue academia?

A: It beats working. No….literally. My Dad was an electrician and he always said he’d kill me if I became an electrician. He and all of his friends worked with their hands and were broken down by the time they were 50. My Dad broke his back on the job and was disabled for 40 years. Against company rules, he borrowed the customer’s ladder. He was trying to save time, but the ladder broke. The other motivation was my Mom. I asked her one day (when I was young, at the height of the Vietnam War) why the world was such an awful place. She said, “somewhere there are great minds working on that very question.” I wanted to know who and she said, “probably at the universities.” So that’s when I decided to become a professor. Who wouldn’t want to be a part of that?

My Dad was an electrician and he always said he’d kill me if I became an electrician.

Q: What institution(s) did you study at in your pursuit of postgraduate education?

A: When I was a senior in college I wrote to Carl Hempel, who was at that time the most prominent living philosopher of science. He recommended five schools, one of which was the University of Michigan (where he had three former students). I went there to study with Jaegwon Kim, who left the following year. I wasn’t very happy at Michigan, at least in part because I had no funding. I had also gotten into the University of Chicago, where I had full funding and likely would’ve studied with the estimable Bill Wimsatt. I’ll always wonder about that. I got an excellent education at Michigan, but back in those days, they beat up their graduate students pretty badly. The attrition rate was terrible. I broke the record for time to Ph.D. at six years, because I wanted to get out of there.

Q: What was the title of your PhD thesis, and how would you explain your findings to a novice?

A: “Problems in the Philosophy of Social Science: A Defense of Nomological Explanation in the Social Sciences.” This became my first book LAWS AND EXPLANATION IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES (Westview Press, 1996). My argument was that there was no methodological difference between the natural and social sciences, which meant that we could discover the laws of human nature. In principle, I still agree with the finding, though these days I think I was on the wrong track. Methodology isn’t what makes science special….it’s values and attitude. But the social sciences are atrocious and could be better if they emulated the natural scientific model. Even without laws, they could be more rigorous.

Q: If you had your time as a student again, what would you do, if anything, differently?

A: Not worry so much. I had more room for error than I thought.

Research Focus

Q: Tell us about your current research focus?

A: I am still fascinated with the question of what is special about science. I’ve always believed that the scientific approach to inquiry allows us both to achieve understanding and use the answers to improve the world. But this means that science deniers are the bane of my existence, so that is what I study these days. I just cannot believe that some people are not convinced by facts and evidence on empirical questions. It both horrifies and fascinates me. So I’m trying to finding the most essential feature of science and use this to fight back against science denial. And I think that I’ve found it.

Science deniers are the bane of my existence.

Q: What do you believe is your single most important piece of research?

A: Without question, I think it’s my most recent book THE SCIENTIFIC ATTITUDE: DEFENDING SCIENCE FROM DENIAL, FRAUD, AND PSEUDOSCIENCE (MIT Press, 2019). It’s the book I’ve always wanted to write. In it I make the argument that the most distinctive feature of science is its attitude toward evidence: the idea that evidence counts and that one has to be willing to change one’s mind on the basis of new evidence. This more than anything — any logic or methodological feature — is what makes science work so well. And then when you compare this to the problems created by climate change deniers or anti-vaxxers….it’s pretty clear what they are missing. Their beliefs are shot through with ideology and wishful thinking. They aren’t being rigorous and don’t even seem to be aware of it. I think my theory also helps us to understand what is so terrible about fraud. And pseudoscience. So after all those years, thinking that what the social sciences needed to do was emulate the methodology of the natural sciences, I’ve decided that this is the wrong thing to emulate. It’s the attitude that scientists have toward evidence that makes their work special. And this is a community ethos that can be shaped by the practices of science, just as it happened in physics, chemistry or medicine.

Q: Within your area of study, what breakthroughs are on the horizon?

A: I am quite fascinated these days by the issues in virtue and vice epistemology. But breakthroughs still to come? I think we need to understand better the sorts of toxic reasoning people engage in when they submit themselves to conspiracy theories or inconsistent standards of evidence. I’ve given up on the “problem of demarcation” between science and non-science. I don’t think logic or methodology is where the next big discovery will be made. I think it will be in psychology or epistemology.

Q: Let your imagination take over for a minute and tell us what you hope your successors will be researching in 2116?

A: How to use the results of the newly revolutionized social sciences to make better policy decisions based on data-driven models.

Q: What do you feel your professional legacy will be?

A: My goal in the last fifteen years has been to write philosophy that will be accessible to a general audience. I hope that my legacy will be to have done something to show that philosophy is an essential part of living a more meaningful life both as an individual and in society. If I can have brought more people into philosophy, that would be wonderful. Of course, I hope my theory of “the scientific attitude” will be successful. But really my focus on science is just part of it. If I could live ten more lifetimes I’d go back and do the same thing in metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics. I think more people need to have their lives informed by philosophical thinking. There should be practitioners of philosophy, not just theorists.

Current Projects

Q: Are you working on any extra-curricular projects at the moment, such as: books, podcasts, websites, or speaking?

A: Right now I’m doing a lot of publicity for THE SCIENTIFIC ATTITUDE. Various speeches and op-eds, a bit of radio, podcasts, and even some TV. My next project is a new book on how to talk to science deniers face to face. I did this at the Flat Earth International Conference in Denver in 2018. It was a life-altering experience. I’ve studied science denial for over a decade and here they all were. Now I’m meeting with other groups on other topics, and I’m going to write a book about it.

Advice and Tips

Q: If you could give your 18-year-old self one piece of advice, what would it be?

A: Calm down. It’s going to be ok.

Q: What advice would you give someone looking to start, or progress his or her career in your field?

A: This fall my son will be starting a Ph.D. program in philosophy at Rutgers, so this is a topic of some interest in our house right now! My best advice is to follow your own instinct about what you are interested in. Don’t just chase the hot topics. Nobody can tell you what you “should” be interested in. And things change. Who could have predicted the emergence of public philosophy over the last decade? There may not be a job at the end of the rainbow anyway, so remember why you got into this. You don’t go into philosophy to be a careerist.

Q: Which book would you say has had the biggest impact on your life?

A: Biggest impact on my career? Conjectures and Refutations by Karl Popper. But that’s not my favourite book. My favourite book is Walden by Henry David Thoreau. I read this at a young age and it really inspired me to think for myself and go my own way. That made a big difference.

Q: If you could recommend one book to a novice in your field, what would it be?

A: There are a lot of obvious choices, but I’m going to recommend one that almost nobody will have read. It’s called The Folly of Fools by Robert Trivers and it deals with the problem of delusion. Trivers (who is a biologist) is one of the most honest thinkers I’ve ever read. Insights galore. If I could recommend just one book in philosophy it would be How Fascism Works by Jason Stanley. It’s a stunning example of what I think is so compelling about philosophy. It’s intellectually rich and applied to one of the most important problems of our time. This book shows what philosophy can do when it aspires to make a difference.

Q: Why do you think being a freethinker is important?

A: What other way is there to be? I don’t believe in an afterlife, so this is it. What a waste if I let someone else tell me what to believe or what to do with my time. I’d rather go my own way. One of my favourite lines in Thoreau is “I’d rather sit on a pumpkin and have it all to myself than be crowded on a velvet cushion.” I also owe it to my Mom. The single best piece of advice she ever gave me was “think for yourself.” Literally, that’s what she said, starting at about the age of 5 and ever since. Her idea was that the times in life when people get themselves into trouble is when they let someone else tell them what to do. If you listen to your own instinct, you’ll almost never go wrong. My Mom had a lot of confidence in me and took me seriously. That was a real gift.

I also owe it to my Mom. The single best piece of advice she ever gave me was “think for yourself.”

Conclusion

Q: And finally, we are back at the dinner party. Someone offers you a drink, what do you ask for?

A: Actually, I don’t drink alcohol. So there’s always that awkward moment. I make it easy on people and just ask for juice or water. I don’t drink coffee either. I’m fairly ascetic. Except for Pepperidge Farm cookies. God help me.

If you’d like to find out more about Dr Lee McIntyre you can check out his personal website, Twitter profile and his Wikipedia page.

Books Recommended by Dr Lee McIntyre

Conjectures and Refutations by Karl Popper

Walden by Henry David Thoreau

The Folly of Fools by Robert Trivers

How Fascism Works by Jason Stanley

The Scientific Attitude by Lee McIntyre

Post-Truth by Lee McIntyre

Advertisement